Hodgkin's lymphoma

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

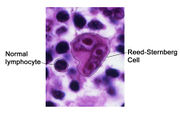

Micrograph showing Hodgkin's lymphoma (Field stain). |

|

| ICD-10 | C81. |

| ICD-9 | 201 |

| ICD-O: | 9650/3-9667/3 |

| DiseasesDB | 5973 |

| MedlinePlus | 000580 |

| eMedicine | med/1022 |

| MeSH | D006689 |

Hodgkin's lymphoma, previously known as Hodgkin's disease, is a type of lymphoma, which is a cancer originating from white blood cells called lymphocytes. It was named after Thomas Hodgkin, who first described abnormalities in the lymph system in 1832.[1][2] Hodgkin's lymphoma is characterized by the orderly spread of disease from one lymph node group to another and by the development of systemic symptoms with advanced disease. When Hodgkins cells are examined microscopically, multinucleated Reed-Sternberg cells (RS cells) are the characteristic histopathologic finding. Hodgkin's lymphoma may be treated with radiation therapy or chemotherapy, the choice of treatment depending on the age and sex of the patient and the stage, bulk and histological subtype of the disease.

The disease occurrence shows two peaks: the first in young adulthood (age 15–35) and the second in those over 55 years old.[3]

The survival rate is generally 90% or higher when the disease is detected during early stages, making it one of the more curable forms of cancer.[4] Hodgkin's lymphoma is one of a handful of cancers that, even in its later stages, has a very high survival rate (~90% or better).[5] Most patients who are able to be successfully treated and thus enter remission generally go on to live long lives.

Patients with a history of infectious mononucleosis due to Epstein-Barr virus may have an increased risk of HL.

Contents |

Classification

Types

Classical Hodgkin's lymphoma (excluding nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin's lymphoma) can be subclassified into 4 pathologic subtypes based upon Reed-Sternberg cell morphology and the composition of the reactive cell infiltrate seen in the lymph node biopsy specimen (the cell composition around the Reed-Stenberg cell(s)).

| Name | Description | ICD-10 | ICD-O |

| Nodular sclerosing CHL | Is the most common subtype and is composed of large tumor nodules showing scattered lacunar classical RS cells set in a background of reactive lymphocytes, eosinophils and plasma cells with varying degress of collagen fibrosis/sclerosis. | C81.1 | M9663/3 |

| Mixed-cellularity subtype | Is a common subtype and is composed of numerous classic RS cells admixed with numerous inflammatory cells including lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells. without sclerosis. This type is most often associated with EBV infection and may be confused with the early, so-called 'cellular' phase of nodular sclerosing CHL. | C81.2 | M9652/3. |

| Lymphocyte-rich or Lymphocytic predominance | Is a rare subtype, show many features which may cause diagnostic confusion with nodular lymphocyte predominant B-cell Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma (B-NHL). This form also has the most favorable prognosis. | C81.0 | M9651/3 |

| Lymphocyte depleted | Is a rare subtype, composed of large numbers of often pleomorphic RS cells with only few reactive lymphocytes which may easily be confused with diffuse large cell lymphoma. Many cases previously classified within this category would now be reclassified under anaplastic large cell lymphoma.[6] | C81.3 | M9653/3 |

| Unspecified | C81.9 | M9650/3 |

_mixed_cellulary_type.jpg)

Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin's lymphoma expresses CD20, and is not currently considered a form of classical Hodgkin's.

For the other forms, although the traditional B cell markers (such as CD20) are not expressed on all cells,[6] Reed-Sternberg cells are usually of B cell origin.[7][8] Although Hodgkin's is now frequently grouped with other B cell malignancies, some T cell markers (such as CD2 and CD4) are occasionally expressed.[9] However, this may be an artifact of the ambiguity inherent in the diagnosis.

Hodgkin's cells produce Interleukin-21 (IL-21), which was once thought to be exclusive to T cells. This feature may explain the behavior of classical Hodgkin's lymphoma, including clusters of other immune cells gathered around HL cells (infiltrate) in cultures.[10]

Staging

The staging is the same for both Hodgkin's as well as non-Hodgkin's lymphomas.

After Hodgkin's lymphoma is diagnosed, a patient will be staged: that is, they will undergo a series of tests and procedures that will determine what areas of the body are affected. These procedures will include documentation of their histology, a physical examination, blood tests, chest X-ray radiographs, computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, and a bone marrow biopsy. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan is now used instead of the gallium scan for staging. In the past, a lymphangiogram or surgical laparotomy (which involves opening the abdominal cavity and visually inspecting for tumors) were performed. Lymphangiograms or laparotomies are very rarely performed, having been supplanted by improvements in imaging with the CT scan and PET scan.

On the basis of this staging, the patient will be classified according to a staging classification (the Ann Arbor staging classification scheme is a common one):

- Stage I is involvement of a single lymph node region (I) (mostly the cervical region) or single extralymphatic site (Ie);

- Stage II is involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm (II) or of one lymph node region and a contiguous extralymphatic site (IIe);

- Stage III is involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm, which may include the spleen (IIIs) and/or limited contiguous extralymphatic organ or site (IIIe, IIIes);

- Stage IV is disseminated involvement of one or more extralymphatic organs.

The absence of systemic symptoms is signified by adding 'A' to the stage; the presence of systemic symptoms is signified by adding 'B' to the stage. For localized extranodal extension from mass of nodes that does not advance the stage, subscript 'E' is added.

Signs and symptoms

Patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma may present with the following symptoms:

- Night Sweats

- Unexplained weight loss

- Lymph nodes: the most common symptom of Hodgkin's is the painless enlargement of one or more lymph nodes. The nodes may also feel rubbery and swollen when examined. The nodes of the neck and shoulders (cervical and supraclavicular) are most frequently involved (80–90% of the time, on average). The lymph nodes of the chest are often affected, and these may be noticed on a chest radiograph.

- Splenomegaly: enlargement of the spleen occurs in about 30% of people with Hodgkin's lymphoma. The enlargement, however, is seldom massive and the size of the spleen may fluctuate during the course of treatment.

- Hepatomegaly: enlargement of the liver, due to liver involvement, is present in about 5% of cases.

- Hepatosplenomegaly: the enlargement of both the liver and spleen caused by the same disease.

- Pain

- Pain following alcohol consumption: classically, involved nodes are painful after alcohol consumption, though this phenomenon is very uncommon.[11]

- Back pain: nonspecific back pain (pain that cannot be localized or its cause determined by examination or scanning techniques) has been reported in some cases of Hodgkin's lymphoma. The lower back is most often affected.

- Red-coloured patches on the skin, easy bleeding and petechiae due to low platelet count (as a result of bone marrow infiltration, increased trapping in the spleen etc. – i.e. decreased production, increased removal)

- Systemic symptoms: about one-third of patients with Hodgkin's disease may also present with systemic symptoms, including low-grade fever; night sweats; unexplained weight loss of at least 10% of the patient's total body mass in six months or less, itchy skin (pruritus) due to increased levels of eosinophils in the bloodstream; or fatigue (lassitude). Systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss are known as B symptoms; thus, presence of fever, weight loss, and night sweats indicate that the patient's stage is, for example, 2B instead of 2A.[12]

- Cyclical fever: patients may also present with a cyclical high-grade fever known as the Pel-Ebstein fever,[13] or more simply "P-E fever". However, there is debate as to whether or not the P-E fever truly exists.[14]

Cause

There are no guidelines for preventing Hodgkin's lymphoma because the cause is unknown or multifactorial. A risk factor is something that statistically increases your chance of getting a disease or condition. Risk factors include:

- Sex: male[15]

- Ages: 15–40 and over 55[15]

- Family history[15]

- History of infectious mononucleosis or infection with Epstein-Barr virus, a causative agent of mononucleosis[15]

- Weakened immune system, including infection with HIV or the presence of AIDS[15]

- Prolonged use of human growth hormone[15]

- Exotoxins, such as Agent Orange

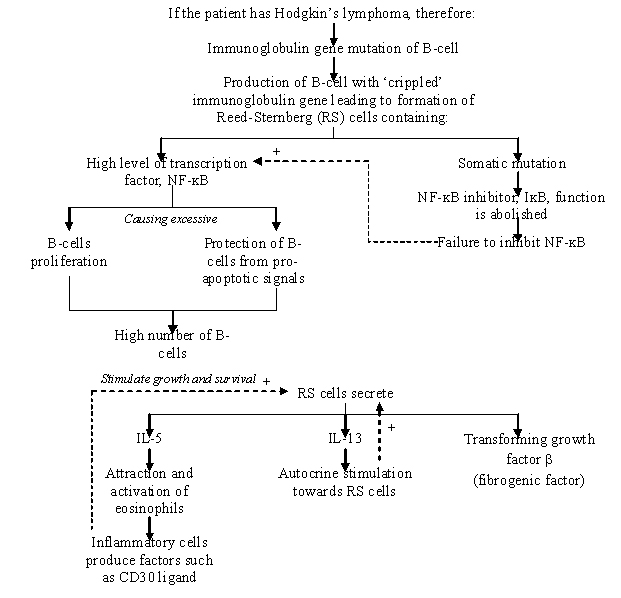

Pathogenesis

Diagnosis

Hodgkin's lymphoma must be distinguished from non-cancerous causes of lymph node swelling (such as various infections) and from other types of cancer. Definitive diagnosis is by lymph node biopsy (Usually excisional biopsy with microscopic examination). Blood tests are also performed to assess function of major organs and to assess safety for chemotherapy. Positron emission tomography (PET) is used to detect small deposits that do not show on CT scanning. PET scans are also useful in functional imaging (by using a radiolabeled glucose to image tissues of high metabolism). In some cases a Gallium Scan may be used instead of a PET scan.

Pathology

- Macroscopy

Affected lymph nodes (most often, laterocervical lymph nodes) are enlarged, but their shape is preserved because the capsule is not invaded. Usually, the cut surface is white-grey and uniform; in some histological subtypes (e.g. nodular sclerosis) a nodular aspect may appear.

A fibrin ring granuloma may be seen.

- Microscopy

Microscopic examination of the lymph node biopsy reveals complete or partial effacement of the lymph node architecture by scattered large malignant cells known as Reed-Sternberg cells (RSC) (typical and variants) admixed within a reactive cell infiltrate composed of variable proportions of lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells. The Reed-Sternberg cells are identified as large often bi-nucleated cells with prominent nucleoli and an unusual CD45-, CD30+, CD15+/- immunophenotype. In approximately 50% of cases, the Reed-Sternberg cells are infected by the Epstein-Barr virus.

Characteristics of classic Reed-Sternberg cells include large size (20–50 micrometres), abundant, amphophilic, finely granular/homogeneous cytoplasm; two mirror-image nuclei (owl eyes) each with an eosinophilic nucleolus and a thick nuclear membrane (chromatin is distributed at the cell periphery).

Variants:

- Hodgkin cell (atypical mononuclear RSC) is a variant of RS cell, which has the same characteristics, but is mononucleated.

- Lacunar RSC is large, with a single hyperlobated nucleus, multiple, small nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm which is retracted around the nucleus, creating an empty space ("lacunae").

- Pleomorphic RSC has multiple irregular nuclei.

- "Popcorn" RSC (lympho-histiocytic variant) is a small cell, with a very lobulated nucleus, small nucleoli.

- "Mummy" RSC has a compact nucleus, no nucleolus and basophilic cytoplasm.

Hodgkin's lymphoma can be sub-classified by histological type. The cell histology in Hodgkin's lymphoma is not as important as it is in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: the treatment and prognosis in classic Hodgkin's lymphoma usually depends on the stage of disease rather than the histotype.

Management

Patients with early stage disease (IA or IIA) are effectively treated with radiation therapy or chemotherapy. The choice of treatment depends on the age, sex, bulk and the histological subtype of the disease. Patients with later disease (III, IVA, or IVB) are treated with combination chemotherapy alone. Patients of any stage with a large mass in the chest are usually treated with combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

| ABVD | Stanford V | BEACOPP |

|---|---|---|

| Currently, the ABVD chemotherapy regimen is the standard treatment of Hodgkin's disease in the US. The abbreviation stands for the four drugs Adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine. Developed in Italy in the 1970s, the ABVD treatment typically takes between six and eight months, although longer treatments may be required. | The newer Stanford V regimen is typically only half as long as the ABVD but involves a more intensive chemotherapy schedule and incorporates radiation therapy. In a randomized controlled study in Italy, Stanford V was inferior to ABVD.[16] | BEACOPP is a form of treatment for stages > II mainly used in Europe. The cure rate with the BEACOPP esc. regimen is approximately 10–15% higher than with standard ABVD in advanced stages. This was shown in a paper in The New England Journal of Medicine (Diehl et al.), but US physicians still favor ABVD, maybe because some physicians think that BEACOPP induces more secondary leukemia. However, this seems negligible compared to the higher cure rates. BEACOPP is more expensive because of the requirement for concurrent treatment with GCSF to increase production of white blood cells. Currently, the German Hodgkin Study Group tests 8 cycles (8x) BEACOPP esc vs. 6x BEACOPP esc vs. 8x BEACOPP-14 baseline (HD15-trial).[17] |

| Doxorubicin | Doxorubicin | Doxorubicin |

| Bleomycin | Bleomycin | Bleomycin |

| Vinblastine | Vinblastine, Vincristine | Vincristine |

| Dacarbazine | Mechlorethamine | Cyclophosphamide, Procarbazine |

| Etoposide | Etoposide | |

| Prednisone | Prednisone |

It should be noted that the common non-Hodgkin's treatment, rituximab (which targets CD-20) is not used to treat Hodgkin's due to the lack of CD-20 surface antigens in Hodgkin's.

Although increased age is an adverse risk factor for Hodgkin's lymphoma, in general elderly patients without major comorbidities are sufficiently fit to tolerate standard therapy, and have a treatment outcome comparable to that of younger patients. However, the disease is a different entity in older patients and different considerations enter into treatment decisions.[18]

For Hodgkin's lymphomas, radiation oncologists typically use external beam radiation therapy (sometimes shortened to EBRT). Radiation oncologists deliver external beam radiation therapy to the lymphoma from a machine called a linear accelerator. Patients usually describe treatments as painless and similar to getting an X-ray. Treatments last less than 30 minutes each, every day but Saturday and Sunday.

For lymphomas, there are a few different ways radiation oncologists target the cancer cells. Involved field radiation is when the radiation oncologists give radiation only to the parts of your body known to have the cancer. Very often, this is combined with chemotherapy. Radiation therapy directed above the diaphragm to the neck, chest and/or underarms is called mantle field radiation. Radiation to below the diaphragm to the abdomen, spleen and/or pelvis is called inverted-Y field radiation. Total nodal irradiation is when your doctor gives radiation to all the lymph nodes in the body to destroy cells that may have spread.[19]

The high cure rates and long survival of many patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma has led to a high concern with late adverse effects of treatment, including cardiovascular disease and second malignancies such as acute leukemias, lymphomas, and solid tumors within the radiation therapy field. Most patients with early stage disease are now treated with abbreviated chemotherapy and involved-field radiation therapy rather than with radiation therapy alone. Clinical research strategies are exploring reduction of the duration of chemotherapy and dose and volume of radiation therapy in an attempt to reduce late morbidity and mortality of treatment while maintaining high cure rates. Hospitals are also treating those who respond quickly to chemotherapy with no radiation.

Prognosis

Treatment of Hodgkin's disease has been improving over the past few decades. Recent trials that have made use of new types of chemotherapy have indicated higher survival rates than have previously been seen. In one recent European trial, the 5-year survival rate for those patients with a favorable prognosis was 98%, while that for patients with worse outlooks was at least 85%.[4]

In 1998, an international effort[20] identified seven prognostic factors that accurately predict the success rate of conventional treatment in patients with locally extensive or advanced stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. Freedom from progression (FFP) at 5 years was directly related to the number of factors present in a patient. The 5-year FFP for patients with zero factors is 84%. Each additional factor lowers the 5-year FFP rate by 7%, such that the 5-year FFP for a patient with 5 or more factors is 42%.

The adverse prognostic factors identified in the international study are:

- Age >= 45 years

- Stage IV disease

- Hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dl

- Lymphocyte count < 600/µl or < 8%

- Male

- Albumin < 4.0 g/dl

- White blood count >= 15,000/µl

Other studies have reported the following to be the most important adverse prognostic factors: mixed-cellularity or lymphocyte-depleted histologies, male sex, large number of involved nodal sites, advanced stage, age of 40 years or more, the presence of B symptoms, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and bulky disease (widening of the mediastinum by more than one third, or the presence of a nodal mass measuring more than 10 cm in any dimension.)

Epidemiology

Unlike some other lymphomas, whose incidence increases with age, Hodgkin's lymphoma has a bimodal incidence curve; that is, it occurs most frequently in two separate age groups, the first being young adulthood (age 15–35) and the second being in those over 55 years old although these peaks may vary slightly with nationality.[22] Overall, it is more common in males, except for the nodular sclerosis variant, which is slightly more common in females. The annual incidence of Hodgkin's lymphoma is about 1 in 25,000 people, and the disease accounts for slightly less than 1% of all cancers worldwide.

The incidence of Hodgkin's lymphoma is increased in patients with HIV infection.[23] In contrast to many other lymphomas associated with HIV infection it occurs most commonly in patients with higher CD4 T cell counts.

History

Hodgkin's lymphoma was first described in an 1832 report by Thomas Hodgkin, although Hodgkin noted that perhaps the earliest reference to the condition was provided by Marcello Malpighi in 1666.[1][2] While occupied as museum curator at Guy's Hospital, Hodgkin studied seven patients with painless lymph node enlargement. Of the seven cases, two were patients of Richard Bright, one was of Thomas Addison, and one was of Robert Carswell.[1] Carswell's report of this seventh patient was accompanied by numerous illustrations that aided early descriptions of the disease.[24]

Hodgkin's report on these seven patients, entitled "On some morbid appearances of the absorbent glands and spleen", was presented to the Medical and Chirurgical Society in London in January 1832 and was subsequently published in the society's journal, Medical-Chirurgical Society Transactions.[1] Hodgkin's paper went largely unnoticed, however, even despite Bright highlighting it in an 1838 publication.[1] Indeed, Hodgkin himself did not view his contribution as particularly significant.[25]

In 1856, Samuel Wilks independently reported on a series of patients with the same disease that Hodgkin had previously described.[25] Wilks, a successor to Hodgkin at Guy's Hospital, was unaware of Hodgkin's prior work on the subject. Bright made Wilks aware of Hodgkin's contribution and in 1865, Wilks published a second paper, entitled "Cases of enlargement of the lymphatic glands and spleen", in which he called the disease "Hodgkin's disease" in honor of his predecessor.[25]

Theodor Langhans and WS Greenfield first described the microscopic characteristics of Hodgkin's lymphoma in 1872 and 1878, respectively.[1] In 1898 and 1902, respectively, Carl Sternberg and Dorothy Reed independently described the cytogenetic features of the malignant cells of Hodgkin's lymphoma, now called Reed-Sternberg cells.[1]

Tissue specimens from Hodgkin's seven patients remained at Guy's Hospital for a number of years. Nearly 100 years after Hodgkin's initial publication, histopathologic reexamination confirmed Hodgkin's lymphoma in only three of seven of these patients.[25] The remaining cases included non-Hodgkin lymphoma, tuberculosis, and syphilis.[25]

Hodgkin's lymphoma was one of the first cancers which could be treated using radiation therapy and, later, it was one of the first to be treated by combination chemotherapy.

Society and culture

Notable cases

Wikinews has related news:

|

- Arlen Specter, US Senator from Pennsylvania, was first diagnosed with Stage 4 Hodgkin's disease in 2005 when he was 75 years old. He underwent chemotherapy treatments without missing a day of work in the US Senate, and subsequently wrote a book, Never Give In, about his battle with Hodgkins. The cancer recurred in April 2008, and he underwent 12 more chemotherapy treatments. In August 2009, he continues to thrive at age 79.

- Don Cohan, oldest U.S. Olympic bronze medalist at the age of 42, diagnosed with Stage 4B Hodgkins disease, defeated it twice, and then won a U.S. championship in sailing at the age of 72.[26]

- Howard Carter, Egyptologist and discoverer of the Tomb of Tutankhamum, died in 1939 from Hodgkin's disease[27]

- Prithviraj Kapoor, a noted pioneer of Indian theatre and of the Hindi film industry died of Hodgkin's disease in 1972.[28]

- Jane Austen, the English writer who created Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice, died of what is suspected to have been Hodgkin's lymphoma in 1817. [29]

- Nancy Mitford, English writer, died of Hodgkin's disease in 1973

- Freida Riley, American school teacher, written about in Homer Hickam's Rocket Boys/October Sky, played by Laura Dern in film October Sky, died of Hodgkin's disease in 1969.

- Paul Allen, Microsoft co-founder, was diagnosed and treated for Hodgkin's lymphoma in 1983.[30] He subsequently developed non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in November 2009[31]

- Lynden David Hall died of Hodgkin's lymphoma in 2006.[32]

- Delta Goodrem, Australian singer, was diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma in July 2003[33]

- Richard Harris, Irish actor, died from the condition in 2002

- Dinu Lipatti, the Romanian pianist, died of Hodgkin's disease in 1950, aged 33[34]

- Craig Wedren, lead singer of Shudder to Think and the lead for the newer pop-mash project, "BABY". In remission.[35]

- Mario Lemieux, National Hockey League forward, was diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma in 1993[36]

- Luke Menard, a finalist on the seventh season of American Idol, was diagnosed with the disease after being voted off the show.[37]

- Starchild Abraham Cherrix, a teenager whose refusal to finish his chemotherapy regimen resulted in a court battle.[38] He is currently battling his fourth recurrence[39]

- Big John Studd, Wrestler John William Minton, died from the disease in 1995[40]

- Brandon Tartikoff, American television executive, died from the disease in 1997.[41]

- Ethan Zohn, Won "Survivor: Africa"[42]

- Daniel Hauser, whose mother fled with him in order to prevent him from undergoing chemotherapy.[43]

- Michael C. Hall, American actor (Dexter, Six Feet Under), in remission as of April 2010.[44]

- Barry Watson, American Actor (7th Heaven), diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma in 2002, in remission as of 2003.

- Glen Goins, American vocalist and guitarist, died of Hodgkin's lymphoma at age 24.

- Wesley Coe, American silver medalist in the 1904 Olympics, died of Hodgkin's lymphoma.[45]

Cultural references

- A main character in the movie October Sky (and the book Rocket Boys), Miss Riley, was diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma.

- In the film Erin Brockovich, Hodgkin's is mentioned as a malaise afflicting one of her clients.

- In the HBO movie 61*, Hodgkin's is mentioned as familial cause of early death.

- The documentary film Crazy Sexy Cancer mentions Hodgkin's.

- In the novel Don't Die, My Love, by Lurlene McDaniel, one of the main characters, Luke, is diagnosed with Hodgkin's and dies after about a year and a half.

- In the latter part of the television series Party of Five, Charlie Salinger (played by Matthew Fox), was diagnosed with Hodgkin's and, through rigorous regimens and treatments, went into remission.

- In the television show Curb your Enthusiasm episode "The Five Wood", Larry David believes his friend's father suffered from "the good Hodgkin's," and that he learned about it from the aforementioned Party of Five series.

- In the movie Sweet November, the character of Sarah Deever (played by Charlize Theron) is in a terminal stage of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

- In Desperate Housewives, the character of Lynette Scavo, (played by Felicity Huffman) is diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma, which she tries to keep a secret.

- Bang the Drum Slowly by Mark Harris is a novel about a baseball player's last season when only he and his best friend know he is dying of Hodgkin's disease. It was later made into a film of the same name.

- In Jeffrey Archer's "Kane and Abel", Matthew Lester is diagnosed with Hodgkin's, but does not disclose his discovery to anyone. His best friend, William Kane, is told by Doctor MacKenzie about the illness shortly before Matthew's death.

- Constable Deirdre 'Dash' McKinley in Australian police drama Blue Heelers was diagnosed with Hodgkins and shaved her head to save herself the trauma of going through hair loss.

- Nuclear Physicist, Nobel Prize Laureate, Richard P. Feynman's beloved first wife might have died of this lymphoma disease after all being accidentally, correctly though, diagnosed by a physician in the hospital where she was hospitalized at the time Feynman was working on the Manhattan Project. The featuring doctor curiously matches the "infamous" character moves of Dr. House in the popular TV show going by the same name. (look also for the story in: Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!)

- In the movie No Escape. the character of The Father, (played by Lance Henriksen) is diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma.

- In the book Cancer Ward by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the character Pavel Nikolayevich Rusanov suffers from lymphoma.

See also

- ABVD

- Ann Arbor staging

- Lymphadenopathy

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, an outdated classification scheme for lymphomas

- Stanford V

Further reading

- Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs. Henry Kaplan and the Story of Hodgkin's Disease (Stanford University Press; 2010) 456 pages; combines a biography of the American radiation oncologist (1918–84) with a history of the lymphatic cancer whose treatment he helped to transform.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Hellman S (2007). "Brief Consideration of Thomas Hodgkin and His Times". In Hoppe RT, Mauch PT, Armitage JO, Diehl V, Weiss LM. Hodgkin Lymphoma (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 3–6. ISBN 0-7817-6422-X.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hodgkin T (1832). "On some morbid experiences of the absorbent glands and spleen". Med Chir Trans 17: 69–97.

- ↑ Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) Caner.gov

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Fermé C, Eghbali H, Meerwaldt JH, et al. (November 2007). "Chemotherapy plus involved-field radiation in early-stage Hodgkin's disease". The New England Journal of Medicine 357 (19): 1916–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa064601. PMID 17989384. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=short&pmid=17989384&promo=ONFLNS19.

- ↑ Stein RS, Morgan D (2003). Handbook of cancer chemotherapy (6th ed.). Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 493. ISBN 0-7817-3629-3.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "HMDS: Hodgkin's Lymphoma". http://www.hmds.org.uk/hl.html. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ↑ Küppers R, Schwering I, Bräuninger A, Rajewsky K, Hansmann ML (2002). "Biology of Hodgkin's lymphoma". Ann. Oncol. 13 Suppl 1: 11–8. PMID 12078890. http://annonc.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12078890.

- ↑ Bräuninger A, Schmitz R, Bechtel D, Renné C, Hansmann ML, Küppers R (April 2006). "Molecular biology of Hodgkin's and Reed/Sternberg cells in Hodgkin's lymphoma". Int. J. Cancer 118 (8): 1853–61. doi:10.1002/ijc.21716. PMID 16385563.

- ↑ Tzankov A, Bourgau C, Kaiser A, et al. (December 2005). "Rare expression of T-cell markers in classical Hodgkin's lymphoma". Mod. Pathol. 18 (12): 1542–9. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800473. PMID 16056244.

- ↑ Lamprecht B, Kreher S, Anagnostopoulos, I, Johrens k, Monteleone G, Junt F, Stein H, Janz M, Dorken B, Mathas S (2008). "Aberrant expression of the Th2 cytokine IL-21 in Hodgkin lymphoma cells regulates STAT3 signaling and attracts Treg cells via regulation of MIP-3a". Blood 112 (Oct 2008): 3339–3347. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-01-134783. PMID 18684866. http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/cgi/content/abstract/112/8/3339.

- ↑ Bobrove AM (June 1983). "Alcohol-related pain and Hodgkin's disease". The Western Journal of Medicine 138 (6): 874–5. PMID 6613116.

- ↑ Portlock CS (July 2008). "Hodgkin Lymphoma". Merck Manual Professional. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec11/ch143/ch143b.html. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ↑ {Hodgon DC, Gospodarowicz MK (2007). "Clinical Evaluation and Staging of Hodgkin Lymphoma". In Hoppe RT, Mauch PT, Armitage JO, Diehl V, Weiss LM. Hodgkin’s disease. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 123–132. ISBN 978-0-7817-6422-3.

- ↑ Asher, Richard (July 6, 1995). "Making Sense". The New England Journal of Medicine 333 (1): 66–67. doi:10.1056/NEJM199507063330118. PMID 7777006.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Hodgkin's disease (Hodgkin's lymphoma) at Mount Sinai Hospital

- ↑ Gobbi PG, Levis A, Chisesi T, et al. (2005). "ABVD versus modified stanford V versus MOPPEBVCAD with optional and limited radiotherapy in intermediate- and advanced-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma: final results of a multicenter randomized trial by the Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi". J. Clin. Oncol. 23 (36): 9198–207. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.02.907. PMID 16172458.

- ↑ Home | German Hodgkin Study Group

- ↑ Klimm B, Diehl V, Engert A (2007). "Hodgkin's Lymphoma in the Elderly: A Different Disease in Patients Over 60". Oncology 21 (8). http://www.cancernetwork.com/display/article/10165/59443.

- ↑ RTanswers.com

- ↑ Hasenclever D, Diehl V (November 19, 1998). "A Prognostic Score for Advanced Hodgkin's Disease". New England Journal of Medicine 339 (21): 1506–14. doi:10.1056/NEJM199811193392104. PMID 9819449.

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2009.

- ↑ Mauch, Peter; James Armitage, Volker Diehl, Richard Hoppe, Laurence Weiss (1999). Hodgkin's Disease. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 62–64. ISBN 0-7817-1502-4.

- ↑ Biggar RJ, Jaffe ES, Goedert JJ, Chaturvedi A, Pfeiffer R, Engels EA (2006). "Hodgkin lymphoma and immunodeficiency in persons with HIV/AIDS". Blood 108 (12): 3786–91. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-05-024109. PMID 16917006.

- ↑ Dawson PJ (December 1999). "The original illustrations of Hodgkin's disease". Annals of Diagnostic Pathology 3 (6): 386–93. doi:10.1053/ADPA00300386 (inactive 2010-01-09). PMID 10594291. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/00300386.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Geller SA (August 1984). "Comments on the anniversary of the description of Hodgkin's disease". Journal of the National Medical Association 76 (8): 815–7. PMID 6381744.

- ↑ Call of the ancient mariner: Reese ... - Google Books. Books.google.com. 2003-10-03. ISBN 9780071388818. http://books.google.com/?id=5bVBhLBis1UC&pg=PA229&lpg=PA229&dq=%22don+cohan%22&q=%22don%20cohan%22. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ↑ James, TGH (2004). "Carter, Howard (1874–1939)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32312. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/32312. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Prithviraj Kapoor and the Prithvi Theatres". Shammi Kapoor. http://www.junglee.org.in/ptheatre.html. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Jane Austen's Illness". http://www.orchard-gate.com/bmj.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ↑ "#41 Paul Allen". The World's Billionaires. Forbes. March 5, 2008. http://www.forbes.com/lists/2008/10/billionaires08_Paul-Allen_1217.html.

- ↑ "Investor Paul Allen Diagnosed With Non-Hodgkin's Lumphoma". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company Inc.. November 17, 2009. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704431804574540513683976836.html?mod=googlenews_wsj.

- ↑ "Soul star dies after cancer fight". BBC News. February 15, 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/4716060.stm. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- ↑ "Singer Goodrem has cancer". BBC News. July 11, 2003. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/music/3057991.stm. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- ↑ Ainley, Mark (2002). "Dinu Lipatti". http://www.markainley.com/music/classical/lipatti/prince_of_pianists.html.

- ↑ "Making a transition into pop simplicity". MSNBC News. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/9927566/. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ↑ Terry, MJ (2002). "Mario Lemieux". Celebrity Survivor Biographies. CureHodgkins. http://www.curehodgkins.com/hodgkins_resources/celebrity_survivors.html.

- ↑ "Former 'Idol' Contestant Luke Menard Has Hodgkin's Lymphoma". Fox News. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,356961,00.html. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ↑ "Teen, court reach agreement over cancer care". Associated Press. MSNBC. September 5, 2006. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/14371567/. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ↑ Matzke-Fawcett, Amy (December 31, 2009). "Musicians rally for cancer victim". The Roanoke Times. http://www.roanoke.com/news/nrv/nrventertainment/wb/231393.

- ↑ "Big John Studd". Hall of Fame. WWE. http://www.wwe.com/superstars/halloffame/bigjohnstudd/bio/.

- ↑ Carter B (August 28, 1997). "Brandon Tartikoff, Former NBC Executive Who Transformed TV in the 80's, Dies at 48". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1997/08/28/arts/brandon-tartikoff-former-nbc-executive-who-transformed-tv-in-the-80-s-dies-at-48.html?pagewanted=1. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ↑ Shanahan M; Goldstein M (May 19, 2009). "Time for 'Grown Ups'". Boston Globe. http://www.boston.com/ae/celebrity/articles/2009/05/19/time_for_grown_ups/. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Minnesota: Evaluation Ordered for a 13-Year-Old With Cancer". Associated Press. NY Times. May 16, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/16/us/16brfs-EVALUATIONOR_BRF.html?_r=1&scp=4&sq=daniel%20hauser&st=cse. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ↑ News-briefs.ew.com

- ↑ Kubatko, Justin. "Wesley Coe Biography and Olympic Results". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com - Olympic Statistics and History.. http://www.sports-reference.com/olympics/athletes/co/wesley-coe-1.html. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

External links

- Hodgkin Disease at American Cancer Society

- Hodgkin's Lymphoma at the American National Cancer Institute

- Information from the German Hodgkin Studygroup (English version)

- Timeline of discovery and treatment of Hodgkin's Lymphoma at hodgkinshistory.com

- Video and information booklet on Hodgkins Lymphoma

- Information on Hodgkins Lymphoma from Lymphoma Research Foundation

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||